This blog gives you the latest topical news plus some informal comments on them from ShareSoc’s directors and other contributors. These are the personal comments of the authors and not necessarily the considered views of ShareSoc. The writers may hold shares in the companies mentioned. You can add your own comments on the blog posts, but note that ShareSoc reserves the right to remove or edit comments where they are inappropriate or defamatory.

In this article, I argue that discounts are bad for those invested in a trust, and the Board of the investment trust should look to reduce any discount. However, for those thinking of investing in the trust the discount might be an opportunity. The question is, how real is that opportunity or is it just a ‘value trap’?

We look at why discounts can arise and the measures that can be taken to eliminate them or even move the trust to a premium. We finish with three case studies to illustrate real-life situations.

Introduction

When an investment trust share price is below its Net Asset Value per share, we say it is trading at a discount.

There are various reasons why an investment trust share might trade at a discount, including:

| Issue | Reasons | What can be done to reduce discounts |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | There are more investors wanting to sell the shares than wanting to buy the shares. | Introduce a buy back policy. This enables those wanting to sell their shares to get a better price. It does however have a downside of reducing the size of the fund and reducing the liquidity and ability to make new investments. Introducing a dividend may increase the number of investors willing to buy and hold the shares. |

| 2. | The track record of the fund manager is poor and investors fear that poor performance will continue. | Change the fund manager. Either require the fund manager to change the investment manager(s) in the team or terminate the fund manager and appoint a new one. If investors approve of this action, then the sentiment towards the trust and the share price should improve. |

| 3. | High fees, which are and if continued will be a drag on performance. | Reduce the fees paid to the fund manager. This is double edged, as the major imperative is to achieve high performance. Halving the fees paid to the fund manager (even if acceptable) may result in the fund manager paying less attention to the investment trust and allocating less able staff to the work. However, paying more than average for poor performance is a waste of money. Merge with another investment trust. This will allow a reduction in fees and hopefully an improvement in performance by selecting the best investment managers from the two organisations that are merged. |

| 4. | Fees based on NAV rather than market cap, fail to incentivise the fund manager to work with the Board to manage the discount. | Change the fee calculation and incentive, so that it is based on market cap and not on NAV. |

| 5. | An inability to raise new funds, which would allow costs to be spread over more funds. | It won’t be possible to raise new funds, but it may be possible to merge the investment trust. |

| 6. | A lack of a buy back policy. | Introduce a buy back policy. |

| 7. | A lack of a fixed life duration and/or continuation votes in the Articles, nor a stated policy to have a continuation vote in a set timeframe. | Announce a continuation vote and future policy. |

| 8. | Directors who do not own significant shares and who are not shareholder friendly. | Directors should buy more shares, so as to signal their belief that the shares are undervalued and that they expect the discount will reduce. Directors should also take all or part of their fees in shares (bought at the market price). |

| 9. | Poor corporate governance. A bad board may be ineffective in managing problems, allow problems to continue or make bad decisions. There are too many boards with too many pale, male, long tenure directors who permit underperformance, discounts, not having continuation votes, etc to continue. Such Boards need to be changed, with an injection of fresh blood, more diversity and greater willingness to get things done. | Shareholders and their representatives should consult with the Chairman to explain their concerns and seek his/her views and agree an action plan to address the discount and other concerns. Remove underperforming directors and replace them with new more diverse directors willing to get things done. This can best be done with the agreement of the Chairman and the majority of the directors; but if not, shareholders can requisition resolutions for the removal of directors. ShareSoc can form a campaign to push for change. The setting up of such a campaign can by itself lead to a change in sentiment and an improvement (reduction) in the discount as well as signalling to the Directors that they will need to change track. |

| 10. | The investments may be in a sector which is out of favour. | |

| 11. | Investors may view the net asset values of the investments in the trust as overstated. | |

| 12. | Investments may have valuations which were correct at the last year end, but market circumstances may have changed and the valuations of investments (when they are next computed) will be lower. |

The liquidity problem

A buy back exchanges the liquidity for an improvement in the discount. By reducing the liquidity in the trust, it reduces the trusts ability to make new investments, thus requiring the trust to not make new investments or to sell other investments and either way the trust shrinks in size, making it less attractive for aspiring investment managers to want to work in the trust.

Further background and examples of what others do:

Duration and continuation votes

These are an important way to ensure the discount does not get too large. For example, Tellworth British Recovery and Growth Trust, which was recently being launched, states in its prospectus:

The Company does not have a fixed life. Under the Articles, the Board is obliged:

-

if the net asset value of the Company as at 31 December 2022 is not at least £150 million, at the annual general meeting of the Company held in 2023; and

-

at the annual general meeting of the Company held in 2026 and at every fifth annual general meeting thereafter,

Share buy backs and discount control policy

For example, Tellworth British Recovery and Growth Trust states in its prospectus its plans to limit the discount to 5%:

The Company has shareholder authority (subject to all applicable legislation and regulations) to purchase in the market up to 14.99 per cent. of the Shares in issue immediately following Initial Admission. This authority will expire at the conclusion of the first annual general meeting of the Company or, if earlier, eighteen months from the date of the ordinary resolution. The Board intends to seek renewal of this authority from Shareholders at each annual general meeting.

The Board recognises the need to address any sustained and significant imbalance between buyers and sellers which might otherwise lead to the Shares trading at a material discount or premium to the Net Asset Value per Share. The Board will aim, through effecting buybacks of the Company’s Shares if necessary, to ensure the Shares do not trade, over the longer term, at a discount of greater than five per cent. to the Net Asset Value per Share in normal market conditions.

In addition, if over the period from Initial Admission to 31 December 2025 the Company’s Net Asset Value per Share total return does not exceed the total return on the FTSE All Share Index, then the Board intends to bring forward proposals that shall provide an option to Shareholders to realise their investment at close to Net Asset Value.

If the Board does decide that the Company should repurchase Shares, purchases will only be made through the market for cash at prices below the estimated prevailing Net Asset Value per Share and where the Board believes such purchases will result in an increase in the Net Asset Value per Share. Such purchases will only be made in accordance with the Companies Act and the Listing Rules, which currently provide that the maximum price to be paid per Share must not be more than the higher of (i) five per cent. above the average of the mid-market values of the Shares for the five Business Days before the purchase is made and (ii) the higher of the last independent trade and the highest current independent bid for the Shares.

ShareSoc director Mark Bentley told me “Buying back shares when discounts are high (and issuing them when at a premium) can help a bit, but the effects are usually transitory.” In his view, more important to reducing discounts is:

- Fundamental performance of the trust. A trust that is not performing well is likely to trade at an increasing discount;

- Strong investor relations, to get the word out about the trust’s performance.

Case Study Harbourvest:

HVPE has been a classic case study. It has been a good performer over the years but used to trade at a persistently high discount. In recent years, however, Harbourvest has made strenuous efforts to connect with investors, presenting regularly at ShareSoc events and also instituting an annual capital markets day, open to all comers, which is a very informative morning (covering the whole PE landscape and economic environment, not just HVPE), with a good breakfast & lunch included. Up until the pandemic, the discount had been reducing steadily (Mark tells me he has taken advantage of the wider discount to buy more).

Case Study JP Morgan Global Growth & Income Trust:

Another interesting factor is dividends. A few years ago, the JP Morgan Global Growth & Income Trust (now JGGI) instituted a dividend policy of paying 4% of NAV as a dividend p.a. Whereas it used to trade at discount (when returns were chiefly as capital growth), it now generally trades at a premium to NAV.

Case Study STRATEGIC EQUITY CAPITAL (SEC):

SEC is a current problem case. There is a long history to the current situation which is explained below.

It is not my place or intent to give financial advice. I will leave it to readers to decide if there may be an opportunity here.

There are a number of ways in which the Board has made decisions which are likely to have led to a persistent and widening absolute and relative discount since February 2017, and especially during 2020:

- Dismay amongst shareholders, of the Board deciding not to implement 6 monthly tender offers, which operated between 2012 and 2014, and were successful in helping the discount narrow markedly. As of February 2017, the market view was that SEC would honour the commitment it made in its 2015 Prospectus to offer tender offers if the discount remained >10%, and as it was also detailed in marketing material provided by the Manager. The Board chose not to re-implement this tender even though the discount went above 10% consistently, and historically the tender offer was effective in narrowing the discount whilst not shrinking the trust. This has led to disaffected shareholders selling to arbitrageurs, which in turn puts off long term shareholders. A vicious circle has been allowed to emerge.

- Ineffective buybacks – insufficient capital used, and it appeared that buy backs were used to only defend a discount of wider than 10%, whereas 10% was the level of the past tenders. This creates a message that the Board considers a 10% discount to be acceptable.

- The Board reduced fees to an uncommercial level and below market level for a trust with this strategy. This has not attracted new shareholders and likely damaged relationship with the management company and portfolio managers, and provided a confused message for investors as to what the trust does.

- With Sir Clive Thompson retiring from the Board, the Board directors own negligible shares. There has been negligible buying since February 2017, despite the widening discount. There has been no buying since the announcement of the Manager change, despite the discount regularly exceeding 20%.

- The Board has given the mandate in March 2020 to a manager who launched the trust and oversaw as portfolio manager a period of very poor performance and material discount widening from launch in 2005 until June 2009. Why is this the right person to improve performance and narrow the discount? Since the change was announced, performance has been poor, and the discount has widened. Moreover, the new Manager has two other very similar products in the same space which is a confusing message and creates multiple conflicts. It also limits the ability of SEC to grow.

- One of the SEC non-Executive Directors had a material conflict in the consideration of Gresham House as the manager of SEC, which was not clearly disclosed.

- SEC’s current marketing material (and other marketing material produced by Gresham House) includes prominent reference to performance which was generated by a lead manager who is not part of the Gresham Team. The Board should have beed aware of this and not allowed it to happen.

Chairman

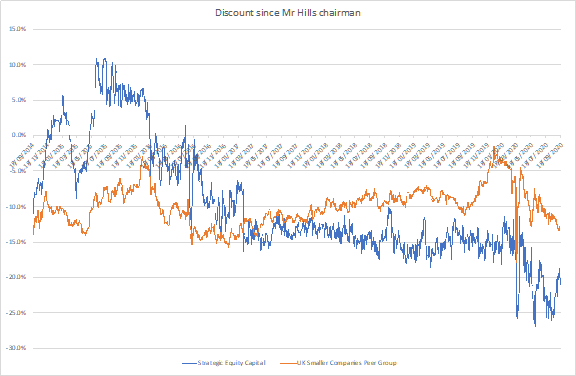

Richard Hills became Chairman on 18 September 2014. He was not part of the Board when there were the deliberations on the introduction of the tender in 2012, and had joined largely when the tender had done its job.

He owns a modest (in my opinion) 75,000 shares in SEC worth £144,000 and is paid an annual fee of £37,500.

SEC use of tender offers

Tender offers were announced in February 2012 and enacted in May and November each year, if the average discount had exceeded 10% in the 6 months preceding 31 December of 30 June respectively. This was an exercise to help reduce the discount over time and the first tender offer was in May 2012. The last tender offer was in November 2014.

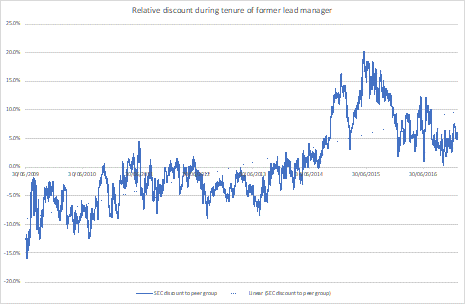

Between November 2014 and February 2017, the discount was narrower than 10% and narrower than the peer group.

The tender offer commitment was also detailed as a discount management policy in the Prospectus dated 3rd August 2015, were the discount to widen to more than 10% again.

Between February 2012 and February 2017, there was a significant change in the shareholder register.

Arbitrageurs (which accounted for >36% of the register prior to the tender offers being started in 2012) were progressively replaced by wealth managers and hnwi & retail investors. One of the considerations of the new shareholders was the discount control mechanism (mechanical) provided by the periodic tender offers, which was also detailed continually as the discount control mechanism in marketing material produced by the Trust’s Manager, then GVO/GVQ Investment Management.

Whilst the tender offers were operating, the trust still grew in size, albeit that the number of shares reduced, and the discount stabilised at a peer average before moving to a premium once the arbitrageurs had exited.

The 2015 Prospectus specifically states that it believes that the mix of performance, broadening shareholder base to institutional and retail investors, and the tender offer was behind the move of the shares re-rating to a premium.

A significant transformation of the register had happened in the two years leading up to his appointment, with all of the arbitrageurs (Fortelus, 1607, Gramercy, CGAM) exiting the register. The last Tender offer was in November 2014 and the discount was already in train of narrowing materially. The new shareholders were all wealth managers and retail investors.

One hypothesis would be that a lot of retail and wealth managers which invested post 2012 in part did so due to the comfort on discount (and liquidity) that the commitment to periodic tenders provided. As they were run on a mix and match basis, there was guaranteed 4% liquidity, at a 10% discount every 6 months. If you owned 4% and were the only holder wishing to exit, you would be able to tender 100% of your holding.

Conclusion

The Tender offers, in conjunction with good performance, were effective and transparent mechanisms to manage the discount.

Since the Board has decided not to honour its commitment to return to the Tender offers, despite there being precedent of them happening before, and them being effective, the wealth managers and retail investors have sold down, and the arbitrageurs have returned (1607 now owns 17%, City of London owns 5.3%). This has coincided with a widening of the discount to above the peer group, which has not been the case since 2012. The presence of arbitrageurs on a register at this level indicates that the wealth management community has “gone on buyers’ strike” and does not trust the corporate governance. Wealth managers rarely vote aggressively, but will just sell down over time.

Extract from Prospectus dated 3 August 2015

Discount management

In February 2012, the Board announced that it proposed to provide Shareholders with semi-annual periodic tender offers for up to 4% of the Shares in issue at a tender price equal to the NAV per Share at the time of the relevant tender offer, less a 10% discount. In line with this policy, tender offers for up to 4% of the Shares in issue have historically been completed in May and November each year since that date, with the most recent tender offer completing in November 2014. When the periodic tenders were introduced, the Board reserved the right not to proceed with any tender offer if, in the six months ending on 31 December or 30 June immediately preceding the relevant May or November, the average discount at which the Shares traded to their underlying NAV was less than 10%. Since 1 January 2015, the Shares have traded at an average premium of 1.5% to the NAV and as at the Latest Practicable Date, traded at a 6.02% premium to NAV.

The Board believes that the move to a premium rating in recent months has been driven by a mix of strong ongoing performance, the Company’s increased profile among institutional and retail investors, the broadening Shareholder base and also the regular tender offers.

The Directors continue to review the level of the discount (if any) between the middle market price of the Company’s Shares and their Net Asset Value on a regular basis and intend to offer Shareholders semi-annual periodic tender offers on the basis set out above if, in the six months ending on 31 December or 30 June in each year, the average discount at which the Shares traded to their underlying NAV is more than 10%.

Board’s comments on discount and discount management

| Report & date issued | Average discount over period | Arbitrageurs | Tender offer/discount comment | Buybacks over the period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interim 2017 Feb 17 | 9.00% | Board will take further action to narrow discount including considering re-introducing tender | Nil | |

| Annual report 2017 Sept 17 | 11.00% | None disclosed (i.e. below 3%) | Discount exceeded 10%, but “the Board does not believe that the re-introduction of the Tender offer is the best way forward as it is a blunt tool which is unlikely to have a long term impact on the Company’s rating” | 975k shares, all of which were between February 2017 and June 2017 |

| Interim Report 2018 Feb 18 | 13.40% | Tender remains under consideration, but not committed to despite average discount 13%. Says using buy backs instead | 1.05m shares bought back. No average discount disclosed | |

| Annual Report 2018 Sept 2018 | 13.50% | 1607 10.5% | No mention of tender. Claims shareholders are supportive of buy back policy. Will buy back when discount is wide. Average discount over year of 13.5% | 1.892m shares (2.8% of issued share capital) at an average 14.4% discount (i.e. 845k shares in h2) |

| Interim Report 2019 Feb 19 | 14.80% | Bought back shares. “board will continue to monitor discount” | 1.945m shares | |

| Annual Report 2019 Sep 19 | 15.20% | 1607 16% | Blames widening discount on the sector discount widening. | 3.231m shares at an average 15.9% discount (i.e. 1.286m in H2) |

| Interim report 2020 Feb 20 | 14.70% | Board will continue to monitor the discount | Bought back 463k shares | |

| Live | 22% |

|

No shares bought back during calendar 2020, despite discount touching 26% |

Notably, the buy backs have been much less than the reduction in issued share capital which would have been provided by the tender offer. The tender offer would also have treated all shareholders equally. The conclusion is that the buy back has been ineffective.

Fees

In Q1 2018, the Board changed management fee reducing it from the lower of 1% of NAV or market cap to 0.75% based on NAV. This removed any financial incentive for the Manager to keep the shares trading at a narrow discount.

The lower fees, combined with a worse performance fee, took the fee base materially below that of the specialist smaller company peer group, and materially adversely impacted the economics for the Manager. This change appears to have made no impact on the discount, will have damaged relationship with the Manager, and probably meant that the Manager withdrew resources. This was even more so as the management fee was now the same as the Manager’s larger open ended fund which was much easier to grow.

Since then, the absolute and relative performance of the NAV has deteriorated. SEC was already a very reasonably priced product for what it did, and I do not believe that any of the shareholders were pushing for lower fees as it was important for the product to be economically viable given the limited capacity of the strategy.

Alignment of interest/director holdings

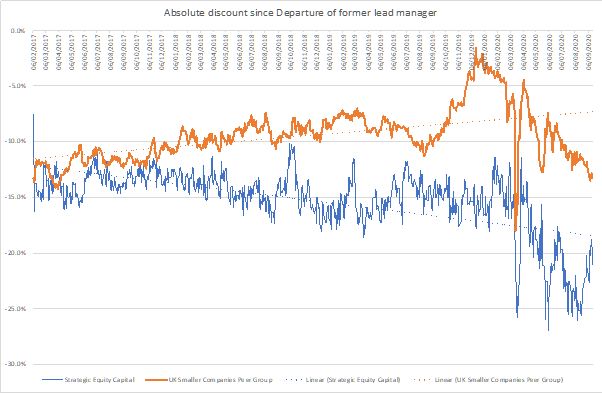

Since Sir Clive Thompson stepped off the board, the Board owns negligible shares. Since Mr Thompson ceased to be a Director, the absolute and relative discount has widened considerably.

| Non-Executive Director | Title | Share Holdings |

|---|---|---|

| Mr. Richard John Hills | Non-Executive Director, Chairman | 75,000 |

| Mr. Richard Locke | Non-Executive Director, Deputy Chairman | 30,000 |

| Mr. David John Morrison | Non-Executive Director | 10,000 |

| Sir William Barlow | Non-Executive Director | 10,000 |

| Ms. Josephine Dixon | Non-Executive Director | 10,000 |

It is interesting to note that they have not purchased any shares since the change of manager announced in March 2020, that they believed would transform the prospects of the Company, and despite the shares trading at more than a 20% discount.

Management group change announced March 2020

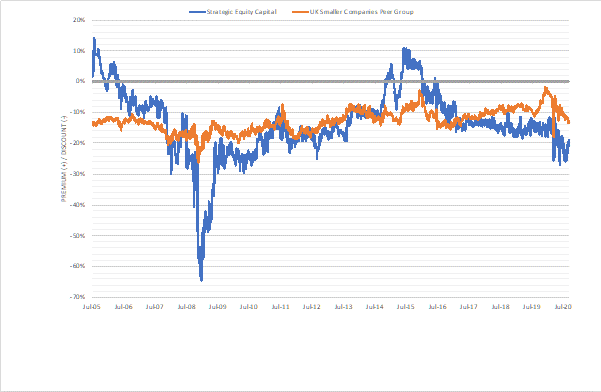

The management contract was changed to an asset management group run by the fund manager who IPOd SEC and managed it until June 2009. He is named as a person who will head the investment committee for SEC going forward. During the period he managed SEC (IPO in July 2005 to June 2009), the absolute and relative performance was extremely poor. The discount widened out materially, at one point reaching more than 50%, and for much of the time Mr Dalwood was running the trust it suffered from a persistently wide discount. It also lost many good long term shareholders and gained arbitrageurs between IPO and June 2009.

Since this was announced, the absolute and relative discount has widened, not narrowed. This indicates that the shareholders/market are not supportive of the Board’s decision. Again, none of the Board members have purchased shares since this change was announced.

As part of the change, in March 2020 the Board announced it would reset the high watermark for the performance fees for the new manager. Such a change would normally customarily require a shareholder vote. There was no explanation for the change. In May the Board changed its mind saying that the old high watermark for performance fees would be retained.

Gresham House already has two other products which do broadly the same thing – the microcap OEIC run by Ken Wootton, and Gresham House Strategic Trust plc (GHS), run by Richard Staveley. These three products are in essence competing with many of the same investments and for many of the same clients. There is no explanation given by the Board of how the inherent conflicts of this situation are managed. With GHS in particular receiving higher management and performance fees than SEC, what is the incentive to put the best investments and sales focus into SEC? Both GHS and SEC are also sub scale.

Other than a brief period at the end of 2019/early 2020, GHS has traded on a persistent discount to NAV and does not have a wide shareholder base of wealth managers. There is no evidence that Gresham House can attract new long term shareholders from the wealth management space to these products in an investment company structure.

GHS was a material and influential shareholder in Be Heard Group when Gresham House was given the mandate for SEC. GHS’s own marketing material states they were heavily involved in appointment and incentivisation of David Morrison as chairman of Be Heard plc, and were large shareholders in Be Heard when they won the SEC mandate. David Morrison is a non-executive director of SEC, and was still chairman of Be Heard when Gresham House was awarded the mandate. There is no mention of these conflicts of interest in the SEC interim report 2020 detailing the change, nor how these conflicts were managed.

Marketing communications

Page 30 of their Q2 2020 investor update (the first under the new management group) shows cumulative NAV growth since June 2009. The chart does not clearly state that from June 2009 until February 2017, the trust had a lead manager who is not part of the Gresham team. It is as if the team is taking credit for someone else’s work.

SEC Summary

The discount for SEC is wider than the average in the sector and has widened recently.

The Board have changed the manager in 2020, but their choice has failed to reduce the discount.

This paper highlights a number of other strategies that might reduce the discount.

Cliff Weight, Director, ShareSoc

DISCLOSURE: The author owns shares in these companies mentioned in this article – Strategic Equity Capital, Gresham House Strategic and Harbourvest.

9 Comments

Leave a Comment Click here to cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

- EDUCATION

- MEMBERSHIP

Digital Marketing by Chillibyte.

I am meeting the Chairman via Zoom on Monday. I wrote to him politely asking for a meeting and sent him a copy of this blog. I look forward to hearing what he has to say.

Schroder Japan Growth (SJG) has bowed to shareholder pressure and offered to buy back a quarter of its shares in four years’ time if the trust’s performance does not pick up.

Annual results this week showed the £222m investment trust underperformed the Japanese stock market for the second financial year in a row. With the shares trading 16% below net asset value (NAV) – the widest discount in its sector – it has pledged to launch a tender offer that would allow shareholders to sell some of their stakes closer to their underlying value in 2024.

The tender offer – which would shrink the trust by up to 25% and risk making it less attractive to big wealth managers – will be triggered unless SJG’s new fund manager Masaki Taketsume (pictured below) decisively beats his Topix index benchmark by more than 2% a year in the four years to July 2024.

i am also invested in GHS- this topic is very helpful and wonder if anyone has looked at the situation with Oakley Capital (OCI) which is a private equity company-any comments from anyone familiar with the matter would be welcome

Ali, I have had a brief look at Oakley. 27% discount. I bought some Oakley shares in Sept. It is another interesting case.

I have written about GHS again today https://www.sharesoc.org/blog/when-is-a-concert-party-not-a-concert-party/

Good to see the number of mergers between trusts is increasing. Latest Press Release (apologies for formatting from my copy and paste, but you can guess the columns!) from AIC says:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 17 JUNE 2024

RECORD YEAR FOR INVESTMENT TRUST MERGERS ALREADY

– Six mergers between investment trusts completed in 2024, with one in the pipeline

– Previous record was five mergers in 2021 and 2022

– See list of 2024 mergers below

There have been six mergers between investment trusts so far in 2024, surpassing the previous record of five mergers set in 2021 and equalled in 2022, according to the Association of Investment Companies (AIC).

The biggest was the merger between Tritax Big Box REIT and UK Commercial Property REIT in May, creating a combined company with total assets of £5 billion.

In addition to the six completed mergers (see table below), a merger between Henderson European Focus and Henderson EuroTrust is expected to complete in July1.

Richard Stone, Chief Executive of the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), said: “A record year for mergers shows that investment trust boards are responding to investors’ preference for larger, more liquid trusts that are easier to trade and cheaper to run. The median investment trust has more than doubled in size from £175 million of total assets ten years ago to £374 million today, excluding VCTs.”

Mergers between investment trusts in 2024

2024

Merged companies (continuing company in bold)

AIC sector

Jan

Henderson High Income

Henderson Diversified Income

UK Equity & Bond Income

Debt – Loans & Bonds

Feb

JPMorgan UK Smaller Companies

JPMorgan Mid Cap

UK Smaller Companies

UK All Companies

Mar

Fidelity China Special Situations

abrdn China

China / Greater China

China / Greater China

Mar

JPMorgan Global Growth & Income

JPMorgan Multi-Asset Growth & Income

Global Equity Income

Flexible Investment

Mar

STS Global Income & Growth

Troy Income & Growth

Global Equity Income

UK Equity Income

May

Tritax Big Box REIT

UK Commercial Property REIT

Property – UK Logistics

Property – UK Commercial

Source: theaic.co.uk (as at 17/06/24)

Number of investment trust mergers by year since 2016

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

to date

No. of mergers

1

2

1

2

1

5

5

4

6

Source: theaic.co.uk (as at 17/06/24)

– ENDS –

I think the tender offer announced on 15 Sept 2025 cannot be accepted by individual investors who own SEC in their ISAs or Personal Pensions (SIPPs) and the pool is not an allowable investment.

https://www.investegate.co.uk/announcement/prn/strategic-equity-capital–sec/tender-offer-for-up-to-100-per-cent-of-issue-/9107194

Surely a rethink is necessary in order to treat all shareholders “fairly”?

i got that first opinion wrong. The shares are tendered and remain an allowable investment.

The tender was accepted by about 22% of shareholders , so the board have managed to get rid of the difficult shareholders e.g. City of London, 1607 and will have an easier ride from the remaining shareholders. Whether this is a good example of good governance is unclear to me. Time will tell. Here is the RNS

Strategic Equity Capital Plc – Result of Tender Offer

15/10/2025 7:00am

UK Regulatory

Strategic Equity Capital (LSE:SEC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2025 to Oct 2025

Click Here for more Strategic Equity Capital Charts.

Strategic Equity Capital Plc – Result of Tender Offer

PR Newswire

LONDON, United Kingdom, October 15

Strategic Equity Capital plc (“SEC” or the “Company”)

Result of Tender Offer

Further to the publication of the circular on 15 September 2025 (the “Circular”), the Board is pleased to announce the results of the tender offer to purchase up to 100 per cent. of the Ordinary Shares in issue (excluding Ordinary Shares held in treasury).

A total of 9,510,496 Ordinary Shares were validly tendered. This represents approximately 22 per cent. of the issued share capital of the Company. The resulting post tender offer Net Asset Value of the Continuing Pool will be above the minimum size condition of approximately £100 million. Based on the Net Asset Value as at 13 October 2025, being the latest practicable date prior to the date of this announcement, the Net Asset Value of the Continuing Pool will be £142,807,766. A final NAV of the Continuing Pool on the Calculation Date of 14 October will be published later today.

Under the terms of the Repurchase Agreement, the Tender Offer may comprise a series of repurchases from Panmure Liberum of a proportion of the Tendered Shares acquired by it from Eligible Shareholders once significant proportions of the assets in the Tender Pool have been realised. This will allow Tendering Shareholders to receive payment for a proportion of their Tendered Shares before all of the assets in the Tender Pool have been realised. The timing of these repurchases will be at the discretion of the Board, and the Company will provide periodic updates via RIS announcements of the progress of the realisation of assets in the Tender Pool. It is currently expected that all of the assets in the Tender Pool will be realised not later than 31 October 2026. If the Directors determine that an Interim Payment should be made, the relevant Tender Price and relevant payment date will be advised via an RIS announcement at the appropriate time.

Following the Calculation Date, the assets of the Company have, as nearly as practicable, been split between the Tender Pool and the Continuing Pool pro rata to the number of Shares referable to each pool. It is the intention that the Company will publish a daily NAV per share announcement for both pools.

As stated in the Circular, the Board intends to continue with the Company’s share buyback programme to manage the discount to Net Asset Value at which the Ordinary Shares may trade, with 50 per cent. of the net gains from realised profitable transactions available in each financial year to fund buybacks of Ordinary Shares, up to a discount of 5.0 per cent. to NAV per Share. Now that the Tender Offer has closed, the Company will be implementing its share buyback policy with immediate effect. For the avoidance of doubt, share buybacks will be funded from the Continuing Pool for the repurchase of Ordinary Shares in the Continuing Pool. If the net gains from profitable realisations cannot be used to purchase Ordinary Shares at a discount to Net Asset Value per Ordinary Share of greater than 5.0 per cent. over an appropriate time period, it is intended that any remaining proceeds will be redeployed by the Investment Manager into investments via the Continuing Pool that are in line with the Company’s investment policy to reduce the potential adverse impact of uninvested cash on investment performance.

Unless otherwise indicated, capitalised terms used in this announcement have the same meaning as given to them in the Circular dated 15 September 2025.

William Barlow, Chairman of Strategic Equity Capital plc, commented:

“With nearly 80% of shareholders not tendering their shares, the board believes this is a strong vote of confidence in SEC’s investment strategy and its portfolio management team.

“As set out when we proposed the Tender Offer, shares which were tendered will now be placed in a Tender Pool, with that capital being returned to Shareholders over the following months, in line with market conditions and the liquidity of the respective investments. We continue to expect this to be complete by the end of October 2026, and will keep shareholders updated.

“We also today reaffirm our commitment to SEC’s share buyback programme to manage the discount to NAV. 50% of net gains from realised profitable transactions will be allocated to buybacks, up to a 5% discount to NAV, as explained in more detail in the Circular. Additionally, a further 100% realisation opportunity will be proposed in 2030.”