This blog gives you the latest topical news plus some informal comments on them from ShareSoc’s directors and other contributors. These are the personal comments of the authors and not necessarily the considered views of ShareSoc. The writers may hold shares in the companies mentioned. You can add your own comments on the blog posts, but note that ShareSoc reserves the right to remove or edit comments where they are inappropriate or defamatory.

This article reflects the opinions of its author and not necessarily those of ShareSoc.

New Financial Report Launched

On 17th October, I attended the launch of New Financial’s excellent report, which was held at the London Stock Exchange. I recommend reading the detailed version (c 35 pages), which I regard as required reading for all serious investors.

My key takeaways:

Swedes are 5 times as likely to invest in shares than Brits. (Around 40% of Swedish adults have a simple and tax incentivised investment account called an ISK, compared with less than 8% of UK adults having a stocks and shares ISA.) Over the past decade, Sweden has become a textbook example of how to nurture the development of capital markets.

The main ingredients have been a redesign of the pension and savings system (starting more than 30 years ago), a high level of retail engagement in capital markets, a deliberate government programme to support the development of capital markets, and tax incentives to encourage the development of tech and growth company clusters.

Valuations and long-term returns

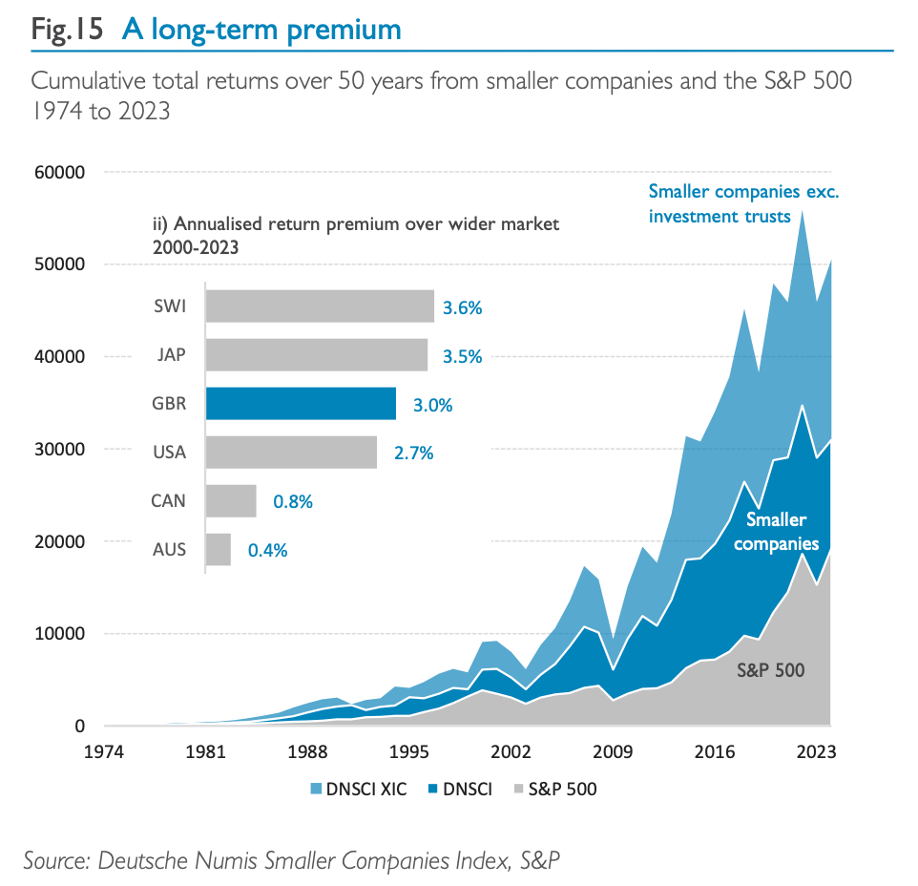

Over the past 50 years – the sort of timeframe that people coming into the workforce in the UK should be thinking of when it comes to their pension – smaller UK companies have delivered an annualised total return of between 12.2% and 13.3% compared with 11.1% for the S&P 500. (It is unclear from their report if the S&P500 figure is in Dollar or Sterling terms. I presume the former. I estimate this is in sterling terms is 12.3%. This is because the £ has been a bad investment since 1974. The £ declined 47% since 1974, from $2.34 to $1.25 at 31/12/2023, i.e. 1.2% p.a. compound on average.) The compound effect of this difference over time translates into more than double the cumulative total return (see Fig.15).

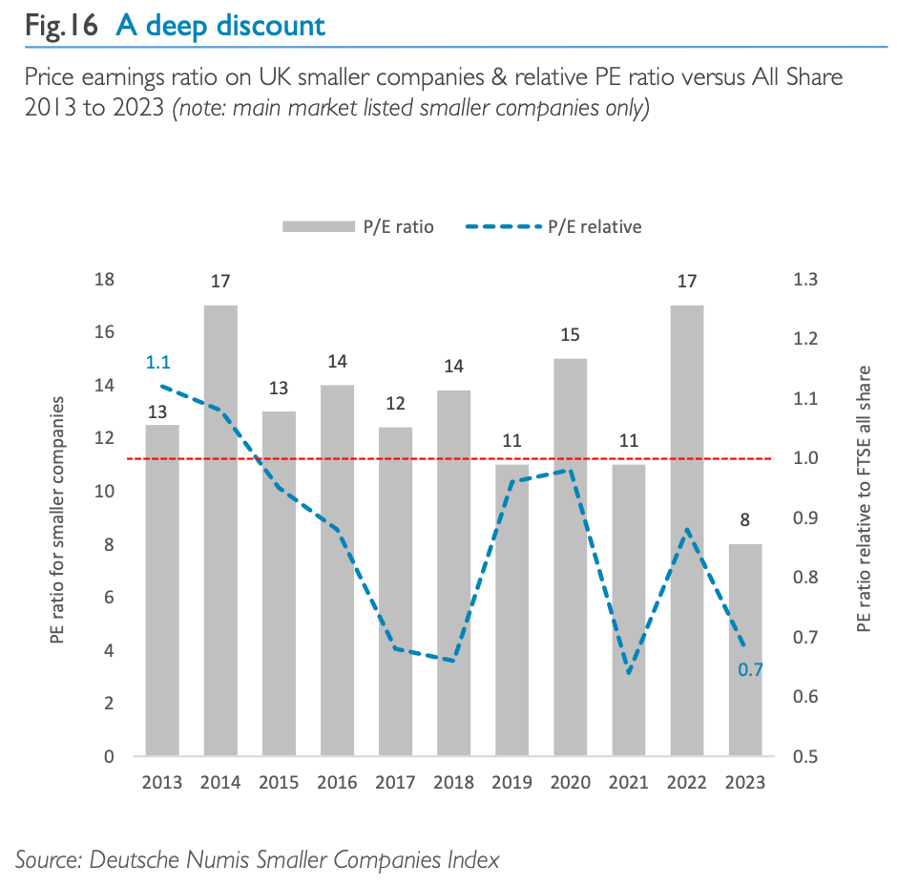

From a valuation perspective, smaller listed companies are arguably trading at a significant discount to the wider UK market (which itself has not been knocking the lights out recently). Fig.16 shows the gradual downwards drift in the average price earnings ratio for UK smaller companies listed on the main market over the past decade. The dotted blue line shows that relative PE ratio compared with the FTSE all share has been falling steadily and that smaller companies have had a lower valuation than the wider market.

If you believe that the smaller company market is not heading towards extinction, the combination of this discount with any future takeover premium may suggest that there is a buying opportunity. (I do, so long as the Labour Government is being honest about its commitment to growth and prosperity and supporting business in the UK!)

UK Regulation stifles growth

In most cases, the debate is not so much about the substance of the reporting but whether the requirements are appropriate for smaller companies given their size and resources. The report’s authors raise the question of where to draw the line between governance from an investment perspective and its use as a proxy for government social policy. While additional reporting makes smaller listed companies more transparent, it also widens the disclosure gap between listed and privately held companies, which contributes to making going public less attractive than staying private.

Part of the challenge with governance is companies and investors struggle to meet each other’s expectations. Smaller companies feel that they should not be held to the same reporting standards as much larger companies, and that there are specific areas (such as the independence of directors) where they should be granted more flexibility. Asset managers used to engaging with much larger firms may have unrealistic expectations of smaller companies and be less willing or able to engage with them to discuss specific concerns.

The Woodford disaster led to more regulation

The FCA responded by focusing on liquidity requirements for fund managers which has led to an industry-wide reluctance to invest in smaller and less liquid stocks. It has also led to more caution in terms of the size of any individual stake in a smaller company with investors keen to avoid going above 5% or 10% of a company’s shares. A natural corollary of this is that more asset managers have moved ‘upmarket’ and have set a higher floor for the size of company in which they will invest (a floor of £100m excludes nearly 60% of smaller listed companies, and a floor of £200m excludes over 80% of them).

Report Key Recommendations included:

Stamp duty: stamp duty on trading in stocks on AIM was abolished in 2014 to boost investor participation in growth companies and help companies raise capital. While successive governments have resisted calls to abolish stamp duty across the whole market, there is a strong case to abolish it for all companies outside the FTSE 100. This would provide a liquidity boost to hundreds of small and mid-cap companies, cost a fraction of the £3.6bn in lost tax receipts from stamp duty , and provide a controlled experiment to help inform the debate on stamp duty across the market.

A short circuit: to specifically boost UK equities, the government could zoom in on the £450bn invested in stocks and shares ISAs and expand the last government’s proposal for a UK ISA (which looks like it may be dropped), and reduce the amount in cash ISAs currently c £400 bn, which produce low returns to savers and are socially useless. This requires education and incentives.

The right balance: resetting the balance between risk and protection should be a particular focus of moving the dial on risk culture. Too often, a narrow approach to consumer protection can lead to the exclusion of retail investors from sensible assets and activities in the capital markets when at the same time they can trade cryptocurrencies and other digital assets in a virtually unregulated free for all environment. (Personally I would add note that at the other end of the risk spectrum is the insistence on the warning that shares can go down as well as up, the modelling of future returns using scenarios of 5% returns, the failure to recognise that small caps have returned 12% p.a over 25 years and the implicit advice to use cash ISAs (despite very low interest rates due to Quantitative Easing), which has caused much consumer harm to those who should have taken on a bit more risk and achieved much higher returns.

++++++++++++

The launch event was a sell out with over 100 attendees and standing room only in the theatre. Sir Douglas Flint introduced the event and then we had a panel session of experts: James Ashton – CEO, QCA; Chris Elms – CEO, Euroclear UK & International; Abby Glennie – deputy head of smaller companies, Abrdn; Marcus Stuttard – head of UK primary markets & AIM, London Stock Exchange Group, and James Wood – corporate analyst, Winterflood.

I was pleased to be invited to ask the second question. I introduced myself as an individual investor and a member of ShareSoc and asked: “Why are UK institutions so reluctant to allow UK growth companies to incentivise their executives with share options? The UK Government has tax favoured EMI options for trading companies with less than £30 million asset and 250 employees. Private Equity uses options to incentivise the executives in investee companies. In the US, tech companies use options to incentivise executives. Why don’t UK Institutional investors follow these practices?”

Panellist Abby Glennie, Deputy Head of smaller companies, Abrdn, was asked to respond and commented that Abrdn had a large group of corporate governance experts and they decided what was best practice and were not in favour of options, preferring LTIPs. This was a disappointing answer, which completely missed my point that smaller companies should be treated differently.

However, James Ashton, QCA CEO, commented that the QCA remuneration guidelines stress that remuneration should be designed to fit the companies’ needs and are flexible and allow the use of share options. This was much more sensible.

ShareSoc’s remuneration guidelines for Smaller Quoted Companies can be read and downloaded here https://www.sharesoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ShareSoc-Remuneration-Guidelines-Smaller-Companies-2018.07.06.pdf. They say:

Share Options are a simple and clear incentive for managers of small companies. The exercise price of share options should be set at not less than the market price at the date of grant. LTIPs and nil cost options, with complex performance conditions are unnecessary for small companies and should not be used.

We believe that a fast growth company should be targeting at least doubling its returns to shareholders (i.e. share price plus dividends) over the planning period. The smaller the company, the larger will be the expectation of growth. Modelling the potential gains, using illustrative changes in share prices, identifies the potential rewards from equity incentives: the company and its shareholders can then decide if the potential rewards are appropriate.

Cliff Weight, ShareSoc and ShareSoc Policy Committee member. Nothing in this article should be construed as financial advice.

DISCLOSURE: The author holds shares in Abrdn.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

- EDUCATION

- MEMBERSHIP

Digital Marketing by Chillibyte.