ShareSoc

INVESTOR ACADEMY

Understanding Corporate Governance and the Regulatory Environment

In this article ShareSoc explains the meaning and importance of good corporate governance and the regulatory environment applicable to you as an investor, to the companies and instruments you may invest in, to the markets you can trade in, and to the brokers/platforms you may use.

Contents

- Introduction

- History

- UK Corporate Governance Code

- UK Stewardship Code

- Listing Rules, Announcements and Market Abuse

- Takeover Panel Rules

- Accounting Rules and Auditing

- The Roles of the FCA, FRC, SFO, BEIS and Others

- Bringing Firms and Directors to Account

- EU Directives

- Important UK Regulations

- Shareholder Rights and Shareholder Committees

- Could Corporate Governance Be Improved?

- Conclusion

Introduction

Why is good corporate governance important for investors? A key reason is that academic studies have shown that there is a correlation between good governance and the returns generated by companies in the long term. Experience over the years has shown that governance failings increase the propensity for bad management, strategic and operational failures.

What is corporate governance? It is the system by which companies are directed and controlled. Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies. Good governance protects shareholders against the worst abuses of rapacious management and against the delusions of over-powerful chief executives. In addition it ensures that shareholders have some voice in the affairs of the company. This article explains how corporate governance operates and how it interacts with financial regulations.

One only has to look back at the events of the banking crisis in 2008 to see that many of the difficulties faced by the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and other banks at the time were caused by over-aggressive management styles, supine boards of directors, poorly constructed financial incentives and other failings.

Good corporate governance can seem a somewhat boring topic to investors who just want to make money. Improved governance does not have an immediate or short-term impact. But it is so important that ShareSoc spends a lot of effort to represent investors on this topic and try to improve the rules that apply to public companies.

Unfortunately many of our members join after losing money due to failures in corporate governance at firms that they invest in, which can result in a total loss of your investment. Carillion is a good example. Please join ShareSoc (which you can do free of charge), if you have not already done so, to show your support for our work to reduce the risk of such failures by lobbying for improved standards of corporate governance and effective, sensible, regulation.

Some History

Why do we need corporate governance? All limited companies in the UK are created under the laws and regulations which are primarily laid down in the Companies Act. The last major revision of that was in 2006 but if you look back to the 1850s when the first similar Acts of Parliament were created, the general principles embodied in them have not changed much. The Acts have grown in size over the years, but there is little in them about how boards of directors are appointed (anyone can be co-opted to the board, and there are no limits on how long they can serve), how they organise their activities, how much they pay themselves and other aspects of importance to investors. For investors, enforcing your rights under the Companies Act is also difficult.

Since the Companies Act of 2006 was passed there have been a number of amendments and Regulations published under the Act – for example on Remuneration Reporting and voting thereon – to try and close some of the obvious gaps so far as investors are concerned, but there is still heavy reliance on good corporate governance principles rather than law.

Corporate governance in the UK was first promoted in the Cadbury Report of 1992 following several unexpected failures of companies. At the same time the death of Robert Maxwell and the demise of Maxwell Communications made it clear that investors had been misled about the financial position of the company by an over-dominant Chairman. There were also the failures of BCCI, Polly Peck and Coloroll, and a few years previously the events at Lonrho, described as the “unacceptable face of capitalism” by Prime Minister Ted Heath.

The Cadbury Report attempted to tackle some of the perceived ills by introducing “best practice” principles for boards with a focus on the financial aspects of companies. Among the proposals were: a) no one individual has sole powers of decision, b) there should be a majority of independent non-executive directors, c) there should be at least three non-executives on an audit committee, d) there should be a remuneration committee of mainly non-executive directors, and e) there should be an independent Chairman. Flexibility was however permitted by a “comply or explain” rule that allowed for justifiable exceptions. The basic principles advocated in the Cadbury Report have been followed in subsequent published Governance Codes, with some elaboration.

Note that the Companies Act and many of the regulations described below only apply to companies registered in the UK. Therefore, when investing in a company it is very important to find out where the company is registered (it should be possible to find this readily in the investor relations section of the the company’s website). For companies not registered in the UK, you should familiarise yourself with the laws and regulations applicable in the jurisdiction in which the company is registered, to determine what rights and protections you have (which may differ significantly from those applying in the UK). For that reason you need to think carefully before investing in any company that is not registered in the UK.

Back to Contents

Current UK Corporate Governance Code

The Listing Rules for public companies (applying to those listed on the Main Market of the London Stock Exchange) require such companies to explain how they have applied the principles in the Corporate Governance Code in their Annual Reports. The latest edition (July 2018) of the UK Corporate Governance Code can be read here: www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/88bd8c45-50ea-4841-95b0-d2f4f48069a2/2018-UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-FINAL.PDF (only 15 pages long). Note that the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) is responsible for maintaining and publishing the Code. Here is a summary of the main points and what is covered:

- Board leadership should ensure an effective and entrepreneurial board, that the company has the necessary resources to meet its objectives and effectively measure performance against them. The board should engage with shareholders and other stakeholders, including the workforce, to ensure long-term sustainable success.

- The Chair should lead the board and there should be an appropriate combination of executive and non-executive directors with no dominance by one individual or group. The Chair should be independent and there should be a majority of independent non-executive directors.

- There should be a “senior” independent non-executive director to act as an intermediary to the Chair for shareholders and other directors.

- A nomination committee should be established with a majority of independent non-executive directors. The committee should ensure succession planning. Directors who have served for more than 9 years are not to be considered “independent” and Chairs should not serve for more than 9 years.

- The board should establish an audit committee of independent non-executive directors. They should monitor the integrity of financial statements and review internal financial controls and audit functions (both internal and external). They have responsibility to recommend the appointment of external auditors.

- The board should explain the principal risks the company faces in the Annual Report, and monitor those risks.

- The board should establish a remuneration committee of independent non-executive directors which will determine the policy for executive director and senior management remuneration, plus the Chair. There are specific rules on remuneration to support alignment with long-term shareholder interests and good practice.

What does “independent” mean when referring to directors? In summary it means not being a former employee (e.g. executive director), not having a business relationship with the company, not having close family ties with the company or its advisers or employees, not representing a major shareholder and not having served on the board for more than 9 years. This is designed to ensure that all directors take decisions on a rational basis, not from personal motives and do not develop too cosy a relationship with the executives.

Note that the principles in the Code have helped to ensure that the worst abuses seen in the past (as perceived by investors) are avoided, but it is by no means a perfect system, particularly as feeble explanations can sometimes be given for non-adherence. Similar codes have been adopted in many other countries. The Code has helped to improve standards in public companies even if it has not altogether stopped the financial collapse of companies at short notice because of defective financial reporting, defective audits or fraud. That particularly applies to smaller companies such as those listed on AIM who are not covered by the UK Corporate Governance Code as they are technically “unlisted”, albeit “traded” companies. See later on AIM companies.

Back to Contents

Investment Companies

Note that the UK Corporate Governance Code applies to all listed companies (i.e. main market UK companies listed on the London Stock Exchange). That covers investment trusts and venture capital trusts (VCTs) even though they have a tendency to allow directors to remain well past the 9 years rule. The Association of Investment Companies (AIC) which is an industry body representing investment firms has its own Corporate Governance Code to which many investment trusts refer in their Annual Reports – see www.theaic.co.uk/aic-code-of-corporate-governance-0 . This is an adaptation of the main UK Code to take account of the differences in investment companies – for example they may have solely non-executive board members. But it can be argued that investment companies are still bound by the UK Corporate Governance Code.

Note that mutual funds or collective investment vehicles such as unit trusts and OEICs are not covered by governance codes primarily because they don’t have conventional boards, and rarely hold general meetings for investors as they are not set up as limited companies.

Back to Contents

AIM Companies

Companies listed on the AIM market of the London Stock Exchange are technically “unlisted” so far as the Companies Act and associated regulations are concerned. But they are “traded” companies and so are still covered by some regulations such as the Companies (Shareholder Rights) Regulations. However they are not bound by the UK Corporate Governance Code. Prior to 2018, there was no obligation for AIM companies to adhere to any governance code but the AIM listing rules were then changed (after some urging from ShareSoc and others) to require them to identity a governance code they would be following – still on a “comply or explain” basis. Many AIM companies have chosen to adopt the Quoted Companies Alliance (QCA) governance code. The QCA represents small and medium sized companies. Its code is more limited in scope than the UK Corporate Governance Code – see www.theqca.com/shop/guides and is designed to avoid some of the more costly obligations of the full UK code, and hence be more appropriate for smaller companies. Unfortunately, the QCA code is not available without cost, but ShareSoc has reviewed it and provided input to the QCA in developing it.

ShareSoc maintains a positive dialogue with the QCA to ensure that investors’ interests are represented.

Back to Contents

UK Stewardship Code

Another relevant code is the UK Stewardship Code – see www.frc.org.uk/investors/uk-stewardship-code . This aims to enhance the quality of engagement between investors and companies to help improve long-term risk-adjusted returns to shareholders and is promoted by the FRC. It is a voluntary code to which asset managers, large asset owners and service companies such as proxy advisors can sign up. It encourages engagement with public companies by monitoring, and intervention when necessary, not simply the voting of shares at general meetings. By exercising active stewardship, investors can pressure boards to improve, where they are deficient.

In the government commissioned “Kay Review” (which ShareSoc provided input to), Professor John Kay identifies the “agency problem”: institutional investors often merely act as agents for their clients and are not affected in the same direct way as individual investors investing their own money by the performance of their investee companies. Historically, individual shareholders, with a direct interest, held a higher proportion of the universe of listed and quoted company shares than is the case nowadays. Due to their direct interest they have tended to engage more actively with company boards, and thus acted as good stewards for those companies. The Stewardship Code encourages institutional investors, who now own the largest proportion of shares, to play a more active role and restore the standards of stewardship. See this page for statistics on UK share ownership.

You can play your part by reading annual reports, attending AGMs and engaging with management at those AGMs. More on that can be found here.

Back to Contents

Listing Rules, Announcements and Market Abuse

When companies list on the main London Stock Exchange, or the AIM market, they agree to abide by the Listing Rules. There are different ones for main market companies and for AIM companies. The former is maintained by the UK Listing Authority (part of the FCA), the latter by AIM. The UK Listing Authority also monitors disclosures by issuers (i.e. companies) and authorises prospectuses for new share issues – see www.fca.org.uk/markets/ukla. The main market listing rules are now contained in the FCA Handbook which is somewhat of a misnomer as it consists of hundreds of pages of regulations that apply to financial institutions (and their employees) and to public companies – see www.handbook.fca.org.uk/handbook.

An example of what it covers are the requirements for disclosure of news by companies (particularly price-sensitive information, i.e. news that might affect the share price). Such news is published in a Regulatory News Announcement (RNS) and such announcements are freely available to investors on the internet (see News Sites). They should be monitored by investors in respect to the shares they hold.

The Listing Rules also define the content of a prospectus (and when one is required) in great detail and the requirement to publish accounts. The FCA is also responsible for the Market Abuse Regulations (MAR) which are now an element in their Handbook – see www.fca.org.uk/markets/market-abuse/regulation. They contain prohibitions on insider dealing, unlawful disclosure of inside information and market manipulation. MAR applies both to fully listed, main market, companies and to AIM companies.

The AIM Listing Rules are somewhat different and have fewer obligations, but do contain a useful requirement (AIM Rule 26) to oblige companies to publish key information about the business on a web site including the last prospectus. Looking for that disclosure on a company’s web site is often a good source of information on AIM companies. The last AIM Rules, published in 2018, are present here: https://docs.londonstockexchange.com/sites/default/files/documents/aim-rules-for-companies-march-2018-clean.pdf

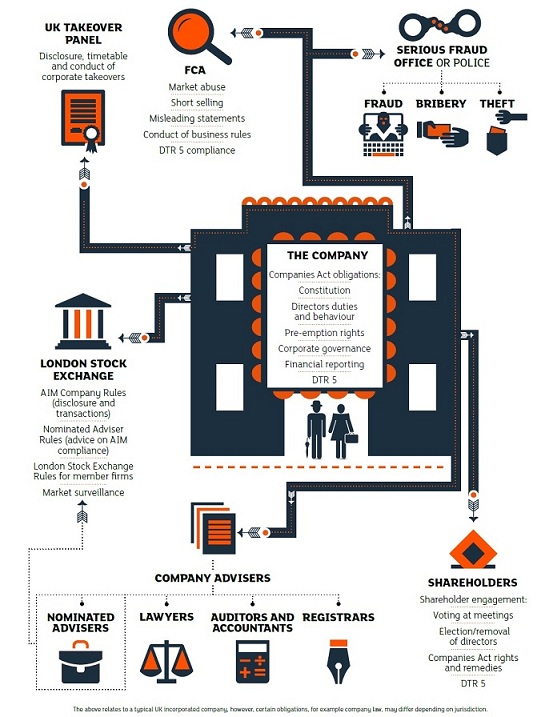

The FCA and AIM do not just publish Rules but also undertake enforcement. In the case of AIM, some of the responsibilities for ensuring compliance rest with appointed Nominated Advisors (NOMADS). The LSE have published the following diagram which shows the interaction between the various regulatory bodies – the main market structure is similar:

Takeover Panel Rules

Another relevant set of rules of interest to investors are contained in the City Code on Takeovers and Mergers which now have statutory authority. This Code reflects the collective opinion of those professionally involved in the field of takeovers as to appropriate business standards and as to how fairness to shareholders and an orderly framework for takeovers can be achieved. The Takeover Panel acts as the regulator to set and enforce the Rules. See www.thetakeoverpanel.org.uk for more information.

Some of the most important rules are that when discussions regarding a potential takeover or merger between two companies become public knowledge (e.g. through a press report), the bidding company needs to make a firm written offer, that is advised to shareholders, within a specified time period. If the bidder fails to do so, or shareholders reject such an offer, the bidder may not bid again for another specified time period (“put up or shut up”).

In addition there is a requirement that a shareholder (or group of linked shareholders, known as a “concert party”) whose shareholding increases to 30% of a company’s shares makes a mandatory offer for the remaining shares in the company. This is designed to prevent “creeping control” to be achieved, disadvantaging other shareholders.

Note though that the Code primarily covers companies that are registered in the UK (or Isle of Man and Channel Islands) and are traded on UK exchanges. So some AIM companies are not covered, for example. More on the impact of takeovers on shareholders can be found here: Understanding Corporate Actions

Back to Contents

Accounting Rules and Auditing

Most UK public companies publish accounts in compliance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) – see www.icaew.com/library/subject-gateways/accounting-standards/ifrs. The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) publishes that standard and acts as the professional body for Chartered Accountants. They act as the regulatory body for professional accountants, set the standards they are expected to adhere to and can handle complaints against them – for example if the accounts prepared for a company are clearly false. The ICAEW also sets standards and regulates the auditing profession. Note: there are other professional and regulatory bodies for accountants that are also relevant such as the ACCA, CAI, CIPFA, ICAS and CIMA.

Back to Contents

The Roles of the FCA, FRC, SFO, BEIS and Others

Given the complex nature of the UK financial regulatory structure, it is often not clear which body is responsible for what and who to complain to when you feel that there is an issue of concern or that you have lost money from investing as a result of failings by company boards, their accountants or auditors. ShareSoc can give members some advice on such matters. But here is some explanation of the respective roles of the FCA and FRC and other bodies at the time of writing (December 2018) although these may change as a result of the current Kingman Review:

The Financial Reporting Council (FRC) maintains the UK Corporate Governance Code and the UK Stewardship Code. It is also responsible for the audit profession and audit standards. It reviews many UK financial reports and the audits performed annually. It also does thematic reviews on financial reporting and auditing and runs “labs” focused on those subjects in which ShareSoc members have participated. The FRC is primarily funded by a levy on the accounting/audit profession and by a levy on listed companies.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the regulator for the many tens of thousands of financial services firms who operate in the UK. The FCA authorises such firms without which they cannot do business, and also authorises some of their staff. Note that the Bank of England, via the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), also acts as the regulator for banks, building societies, insurance companies and some major investment firms – some firms can be regulated by both the FCA and PRA. The FCA also regulates financial markets in general.

The FCA is funded by the firms it regulates and it reports to the Treasury and to Parliament. Its work and purpose is defined by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). It publishes a Handbook and other guidance on how regulated firms should operate and the rules to which they must adhere – see www.handbook.fca.org.uk.

Note that the FCA does not handle individual and specific consumer complaints concerning financial services providers (e.g. complaints about stockbrokers from individual investors who the FCA regard as “consumers”). These need to be dealt with by the Financial Ombudsman Service or by a court legal claim (e.g. in the Small Claims Court which is a relatively simple process). But it does handle wider issues such as market abuse in financial markets.

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) also has a role in regulating companies and includes the Competition & Markets Authority, Companies House where all UK companies are registered, and the Insolvency Service. BEIS has the power under the Companies Act to appoint inspectors to investigate the affairs of any limited company – for example in the case of suspected fraud or false trading when it can potentially apply to a court for a company to be wound up. BEIS also has the power, generally through the Insolvency Service, to apply for unfit directors to be disqualified via the courts.

The Serious Fraud Office (SFO) investigates and prosecutes serious or complex fraud, bribery and corruption. It tends to focus on larger firms with international significance. For example it recently (in 2018) pursued Tesco and some of its executives over past false accounts – more on that below. Complaints about smaller firms in cases where fraud or false accounts are alleged would tend to be handled by the FCA and/or FRC, or sometimes other bodies such as the City of London Police who specialise in fraud cases.

Back to Contents

Bringing Firms and Directors to Account

You can see from the information above that regulation of UK companies is exceedingly complex in that knowing what to complain about and to whom is often not easy to answer. ShareSoc members can consult us for advice on how to complain or seek remedies for perceived wrongs. We will do our best to assist and support you, if we believe your complaint is justified. The regulatory authorities and the various Acts of Parliament that are relied upon, seem to be both bad at preventing financial crime and dubious behavior but also at bringing to account those people or companies at fault. That has always been so since joint stock companies were first invented. However there are some glaring problems that could be tackled. These include:

- The ability of individual company directors to claim that they took sound legal or other advice that justified their actions, i.e. they relied on others who are rarely in court.

- The inability to prove to courts that individuals both knew that what they were doing was illegal and had control over events. This was why the SFO case against Tesco caused the company to accept a Deferred Prosecution Agreement, but the prosecution of individuals was thrown out by a judge before it was even considered by a jury on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

- The fact that these cases often take years to come to court by which time some of the individuals are ill (e.g. again in the Tesco case), are dead, or can plead mental or physical incapacity. The Guinness case showed how quickly some defendants can recover thereafter however. The victims can also tire or die if a case runs for many years.

- The fact that litigation is enormously expensive in the case of corporate misdemeanours. These are always High Court cases and the expense is rarely justified for investment institutions let alone individuals. Big companies can often fend off cases by delaying and running up the legal bills of complainants meaning that cases get abandoned or that the complainants have to rely on third party litigation funders at great expense – examples were the claims against the Royal Bank of Scotland over their rights issue prospectus in 2008 – settled ten years later, and the claim against Lloyds over the acquisition of HBOS.

- The fact that companies are often unwilling to pursue former employees or directors but rather “move on”. That also applies to administrators where the company has gone into administration. One possible solution is to use a “derivative claim” but such legal actions are rare.

The US seems to act in a firmer manner against miscreants and has stronger legislation to protect shareholders. ShareSoc would like to see similar legislation introduced in the UK, making corporate fraud a crime.

Note that Shareholder Action Groups are a way for investors to both bring pressure to bear on errant companies and to formalise complaints and legal action. ShareSoc has supported some such groups in the past. For more information see: Shareholder Action Groups.pdf

Back to Contents

EU Directives

Much of the UK regulatory landscape is now dictated by EU Directives which lay down regulations that apply across the EU. They are typically incorporated into UK law by amending UK Acts of Parliament or by Regulations, although some flexibility on how the Directives are implemented is usually permitted. That will continue to be so whether we proceed with Brexit in 2019 or not because even if we do the intent is that there will be some harmonisation with EU financial directives. EU Directives that affect financial markets are:

- Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFM) for investment funds.

- Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) for bank capital.

- Markets in Financial Instruments Directive 2004 (MIFIR, MiFID-I, MiFID-II ).

- Transparency Directive that covers financial reporting.

- Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities Directive 2009 (UCITS).

- Prospectus Directive.

- Shareholder Rights Directive (SRD and SRD-II).

- Market Abuse Directive (MAD).

The Shareholder Rights Directive is potentially very important in the following areas, although UK company law already covered several aspects fully:

- The conduct of general meetings and the answering of questions.

- The disclosure of shareholders and their identification.

- The exercise of shareholder rights including proxy voting particularly as regards beneficial owners (i.e. those in nominee accounts).

- The information transmission to shareholders.

ShareSoc is a member organisation of Better Finance, a pan-European organisation that represents individual investors and we seek to influence the European regulatory landscape via Better Finance.

Back to Contents

Important UK Regulations

There are a number of Regulations that help investors in various ways, in addition to provisions in the Companies Act. These include the right to obtain information on the shareholders in a company so that you can communicate with them, and how general meetings should be run including the requirement to answer the questions of shareholders. Useful ones are:

- Companies (Shareholders’ Rights) Regulations 2009

- The Companies (Company Records) Regulations 2008

- Companies (Fees for Inspection and Copying of Company Records) Regulations 2007

- The Large and Medium-sized Companies and Groups (Accounts and Reports) (Amendment) Regulations 2008 and 2013 which cover financial reporting and remuneration.

Note that some regulations only apply to main market, i.e. “Listed” companies on the Main Market and hence not to AIM companies or those listed on other exchanges.

Back to Contents

Shareholder Rights and Shareholder Committees

Shareholders are particularly interested in rights to receive information – for example an Annual Report and the Notices of General Meetings – and voting rights including the ability to submit proxy votes, directly or indirectly. Shareholder rights are particularly problematic now due to the widespread use of nominee accounts as opposed to shareholders being on the share register and hence being a “Member” of a company under the Companies Act. There is extensive discussion of that issue here: www.sharesoc.org/campaigns/shareholder-rights-campaign/

Corporate governance rules attempt to improve the long-term performance of companies and control inappropriate behaviour. But in many regards, ultimately shareholders need to exercise their influence to restrain the directors or to encourage them to take positive action. Prevention is better than cure on financial matters because going to law over past failings is not only expensive but may not rectify the problem or enable recovery of losses. For example, if a company chooses to make an acquisition that is misconceived for any number of reasons it can be impossible to later unwind or take legal action over the matter. Shareholders need to positively influence corporate strategy if they are to achieve good long term investment returns (see corporate stewardship above).

When it comes to directors’ remuneration the UK Corporate Governance Code gives some guidance on how it should be determined and there are extensive rules on how remuneration is reported (see the Listing Rules) in main market companies. There is also a legal requirement for both advisory votes on past remuneration and binding votes on remuneration policy. But only by exercising their votes on the latter do shareholders have real control over remuneration.

ShareSoc also advocates the use of Shareholder Committees to enhance corporate governance and engagement between shareholders and boards of companies – see www.sharesoc.org/Shareholder Committees.pdf and Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Shareholder Committee Campaign

Back to Contents

Could Corporate Governance Be Improved?

The UK Corporate Governance Code has improved matters in main market listed companies. And governance of AIM companies is improving although there are still significant problems mainly due to poor regulation and enforcement. However governance codes are still ineffective if directors fail in their duties. That can arise from their lack of independence, lack of knowledge of the industry in which the company operates (there is still too much of an emphasis on the “gifted amateur” in the UK), having too many roles to adequately perform their duties (the problem of “over-boarding” on which ShareSoc has issued some guidance – see www.sharesoc.org/Non_Execs_Code.pdf), an unwillingness to stand out against the views of the executive directors or chairman and for many other reasons. Boards of directors can still be dysfunctional.

For example, the board of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) seemed unable to restrain the aggressive and unwise empire building of Fred Goodwin and Northern Rock had a Chairman (Matt Ridley) who was an author and journalist with no banking experience when they became over-reliant on short term money market borrowing. Indeed it was common at the time of the banking crisis to see the boards of banks dominated by those with no banking or other relevant financial experience.

Non-executive directors are still selected on the basis of how they might “fit in” to the culture of a board and they often have similar backgrounds, i.e. there is a lack of diversity that leads to “group-think”. For example, non-executive directors who stand out against the views of the executive directors on pay may soon find that they do not remain on the board for very long.

Shareholder committees are one approach that aims to solve such problems by taking board appointments and remuneration out of the sole control of board directors. Other stakeholders in a company (e.g. employees, suppliers, customers) can also have a positive influence although there are few ways in which they can bring their views to bear at present.

Back to Contents

Conclusion

Good Corporate governance helps to improve company performance and avoid major mistakes by company directors. Effective regulation and shareholder influence also help. But governance needs to be applied both effectively and wisely.

Roger Lawson 15/12/2018 (Last revised 06-Jun-2020 Mark Bentley)